Selective Anality

The Pseudo-Dictionary of Rick Selective Anality: a psychological dysfunction characterized by extreme levels of attention to detail or process in certain areas of one’s life and utter disinterest in any details of other areas. See also: bipolar.

As mentioned in my last post, we have a tradition of having good friends to the house on New Year’s Eve. A key piece of the tradition is that after waking up on New Year’s Day, rubbing the sleep from our eyes, and drinking copious quantities of coffee, friend Charlie and I head out for some form of exercise. Typically it’s a run, but it might be a bike ride or a hike or even lifting weights. This year we stuck with the run, and we went out for an easy 6 miles.

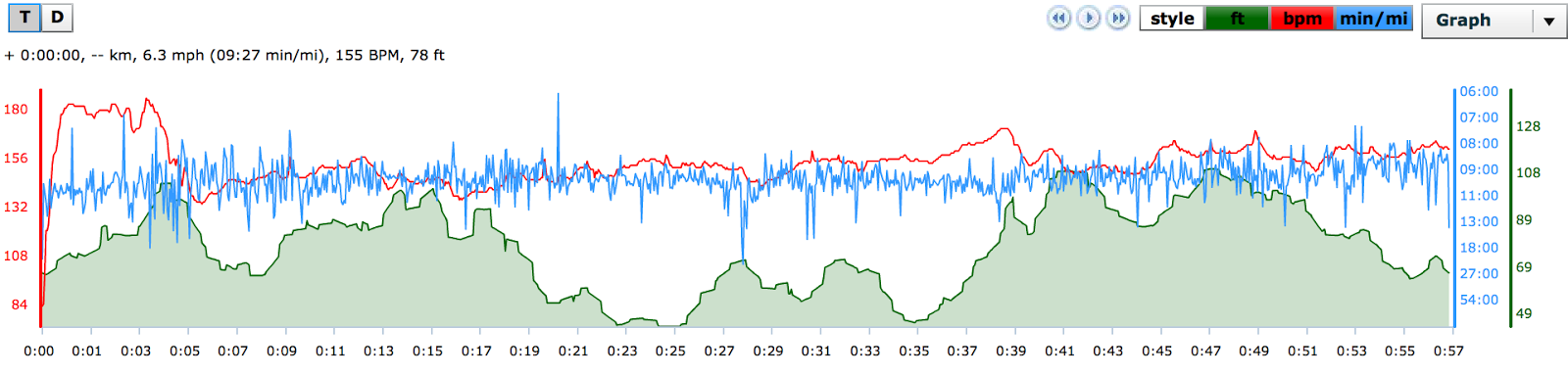

Charlie had just received a GPS watch for Christmas and was trying it out for the first-time. I’ve had one of these (a Garmin Forerunner 305) for about 3 years, and couldn’t imagine running without it. The watch gives me real-time speed, distance, and heart-rate. I can glance down at any time during the course of the run and see how I’m doing. And here’s what’s even better: I can link the watch to my computer and download every gory detail from every second of the run. The software I use for this, TrainingPeaks, then gives me a number of statistics that I can use to gauge the quality of the workout, my current level of fitness, and my current level of fatigue, among many many other details. Here’s a snapshot of my run with Charlie:

Ah, the beautiful data!

Ah, the beautiful data!

This image shows my heart rate (the red line), the pace in minutes per mile (the blue line), and the elevation (the green). Look at all this beautiful data! What can I do with it? Well, I can stare at it, analyze it. I can look at my speeds and see if I’m getting faster, or see if my heart rate gets lower for a given pace, or just congratulate myself for doing the workout, and I’ve got the proof. I have a similar tool for my bike (my Cyclops PowerTap power meter). Every workout I do gets logged in Training Peaks.

As Charlie and I were warming up during the first mile, we were comparing the speed readouts to see how close they were. The watches can tell you your pace right now, or they can give you an average. Due to how they work, the current pace tends to be wildly inaccurate. You might be running a consistent speed, and the watch can fluctuate plus or minus 30 seconds a mile every couple seconds, although it usually seems reasonable. In this case, the speeds our watches were indicating were pretty close to each other, around 5-10 sec/mile apart. This conversation then turned towards a debate on the accuracy of GPS versus maps versus cycling computers. (I’ll leave out the heated discussion of how much different tire pressures can change the diameter of a bicycle wheel, and how that might influence the speed indicated by a cycling computer, which uses a magnet attached to a wheel spoke and a sensor on the front fork to determine the revolutions per minute, and thus the speed, and thus, the distance traveled. Even as I write that, it sounds terribly pedantic.)

This discussion really started a month ago, when we ran the Annapolis Half-marathon together. I was wearing my trusty Garmin. As is the case with most running road-races, there are markers at every mile. As we passed each one, my Garmin never agreed that it was actually that mile. For example, at mile 5, my Garmin read 4.7. At mile 10, it read 10.25. Strangely, at mile 7, it read 7.01. Each time, I mentioned the inaccuracy to Charlie, and he kept telling me to give him the watch. Having my best interests at heart, he wanted me to stop focusing on it, and enjoy the race. Live in the moment, Carragher! In any case, as we sprinted to the finish, a quick glance at my watch told me my time was great (2:04:42) but that the distance was 12.89 miles. A half-marathon is supposed to be 13.1.

For me, this was a major problem. Was my time legit? Should I add 2 minutes? Should I not say we did a half-marathon? I was extremely angry with the race organizers for planning such a poor course (that race in general was generally poorly organized, so I certainly wasn’t surprised that they’d be off by 0.21 miles). I was angry with USATF for certifying the course. I was angry. I wasn’t too angry, since I felt good and had a good race, but there was this nagging feeling that my accomplishment wasn’t really an accomplishment, that it would have an asterisk to it, like Barry Bonds’ home run record, which is almost as important as my Half-marathon in Annapolis, MD. In the drive back to the hotel, I calmed myself, and started feeling good about my effort and the race and the companionship with Charlie.

Then I went back to the hotel room and downloaded the data from my watch. TrainingPeaks plots the Garmin data onto a Google Map, and let’s Google calculate the distance as well. Google tells me that I ran 13.1!

Ahhhh, the GPS was inaccurate! It was confused by the trees or the buildings or the heavy fog we ran through for most of the race. Maybe the proximity to the Naval Academy was the culprit - there are rumors that the US Government mucks with GPS accuracy close to government buildings. In any case, the terrible feeling of wrong-ness was now fully dissipated. I did run a half-marathon, my time was legit, and I can say that I beat my stretch goal of 2:05 for the race.

As Charlie and I get to the half-way point in our run, he reaches down to his fuel belt and grabs his gatorade and takes a swallow. I ask him with a smirk how it tastes. “Perfect”, he answers.

Before we left for our run, he was rummaging around for Gatorade. I normally have some bottles in the garage, but I had recently switched to the powdered variety. I invited him to make some. He started reading the instructions. “One scoop makes 36 ounces”. He needed only 12 ounces for his fuel belt bottle. I said, “Dude, eyeball a third of a scoop, put it in the water and taste it. If it tastes good, you’re good, otherwise add more powder or more water to adjust.”

That didn’t work for him. He figured out a way to make the drink right, to his specifications. He got out a different measuring cup and a tablespoon and worked out the proper mixture.

And that’s kind of the point. I’m incredibly focused on the accuracy of my workout data. And I could care less about the precision of my gatorade mix. Charlie, on the other hand, doesn’t need this level of accuracy for his runs. As we pulled into my neighborhood at the end of our run, I told him, “Bad news.”

“What?”

“When we get to my driveway, we’ll only be at 5.87 miles. We need to go past to get to 6.”

“What! 5.87 is good enough! Great run!”

Nope. I literally can’t do that and feel good about my run. We jog the 0.13 miles past my driveway and walk it in from there. Charlie, the good friend that he is, stayed with me.

As I recover, I dump some gatorade powder into an unmeasured glass of water and drink it down. Because that doesn’t matter. To me. But I feel great about my 155 average heart rate, the average pace of 9:27 minutes per mile, and the 91.6 points of training stress.